Using nitrogen-fixing bacteria to combat malnutrition in DRC

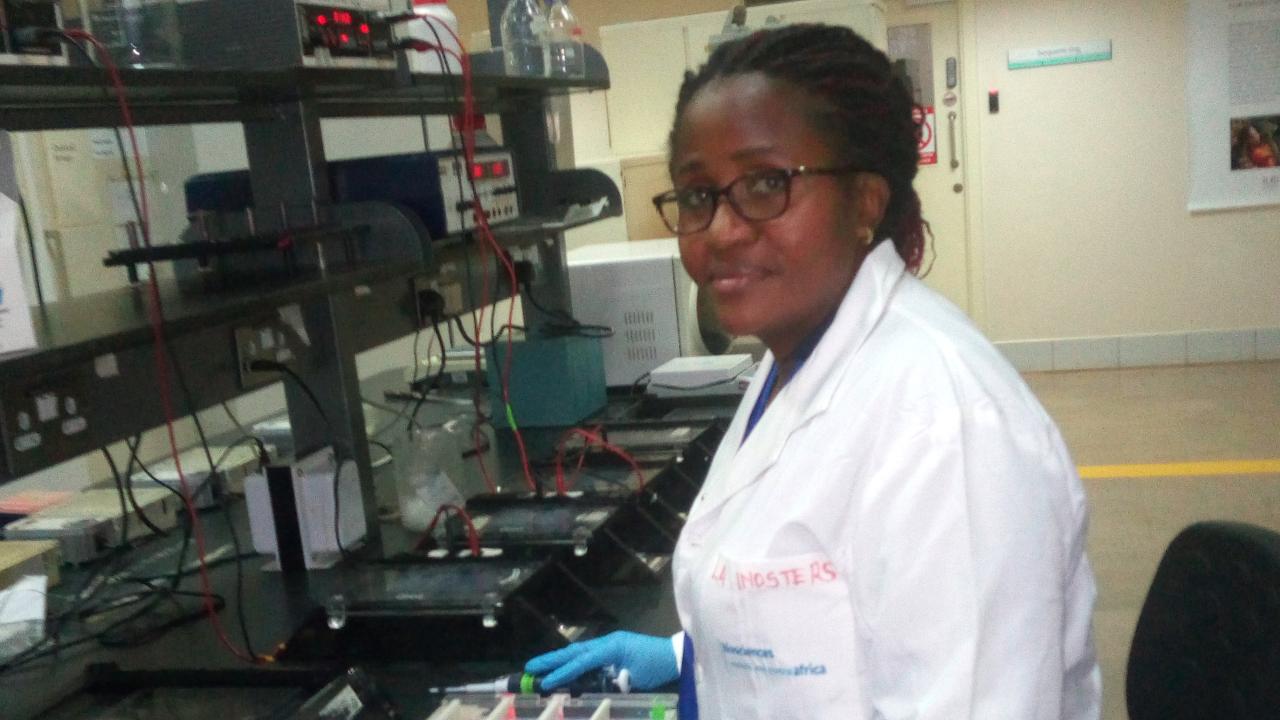

Bintu Ndusha Nabintu, a 2016 fellow from the Democratic Republic of Congo, is currently completing a full-time PhD fellowship at the University of Nairobi in Kenya, where she is researching how to use nitrogen-fixing bacteria to improve the productivity of soybean plants and combat malnutrition in DRC.

How did you learn about the OWSD fellowship, and what difference has it made to your career?

I learned about the fellowship through the Regional Universities Forum (RUFORUM) newsletter in 2014, and applied that year. Unfortunately, my application was not selected but I did receive useful comments that I took into serious consideration. In 2016, I applied again and this time I was selected. The fellowship has really impacted my career. I was working in a university as an Assistant Lecturer, but with the OWSD fellowship I am undertaking a PhD that will allow me to reach the grade of Senior Lecturer.

What are you researching? What first made you interested in this subject?

My research is on soil microorganisms. I am studying the genetic diversity of indigenous rhizobia, a group of bacteria that fix atmospheric nitrogen in symbiotic relation with legumes. I identify elite strains of rhizobia native to the Democratic Republic of Congo that can be included in fertilizers to enhance the nitrogen fixation—and thus the productivity—of soybeans in the country.

My interest in this subject is guided by the fact that soybean is a very nutritious crop, used to treat malnutrition that is prevalent in DRC due to repetitive wars. Soybean cultivation has been promoted and is expanding very rapidly as a result of its diverse uses and potential to generate cash income for poor households. Despite its importance, the yields reported by the FAO are very low (only 0.5 tons per hectare in 2017). Low soil fertility and limited use of mineral fertilizers, which tend to be exorbitantly expensive for poor farmers, are among the major factors contributing to low soybean productivity in the South Kivu province. Exploitation of biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) in legume crops through rhizobia is an affordable and sustainable approach to improve soil fertility. Therefore, knowledge of in-situ microbial diversity is important to improve this nitrogen fixation and enhance productivity.

Has anything surprised you about your research experience?

During my research I found a very high diversity of indigenous rhizobia and, surprisingly, I discovered that six native rhizobium strains had a close genetic relationship with a commercial strain, USDA 110. In the field, however, two of the native strains outperformed USDA110, increasing soybean grain yield by 68.7% and 70.8% respectively, over the commercial strain.

What are your plans for the future? What will you do after you complete your PhD?

My plan for the future is to be an excellent lecturer and a leading researcher in my region in the domain of soil microbiology and sustainable agriculture. My plan is also to inspire, encourage and support women in their academic and research careers.